The Pantheon: A Temple to All Gods

Built by Romans in 126 A.D. in Rome, Italy, the Pantheon is the oldest, continuously used structure in history. The dome was and is a marvel of engineering and the design of the dome plus columns inspired domed landmarks worldwide.

Michelangelo (1475–1564) looked at everything with an artist’s critical eye, and he was not easily impressed. But when Michelangelo first saw the Pantheon in the early 1500s, he proclaimed it of “angelic and not human design.” Surprisingly, at that point, this classic Roman temple, converted into a Christian church, was already more than 1350 years old.

What’s even more surprising is that the Pantheon, in the splendor Michelangelo admired, still stands today—another 500 years after he saw it.

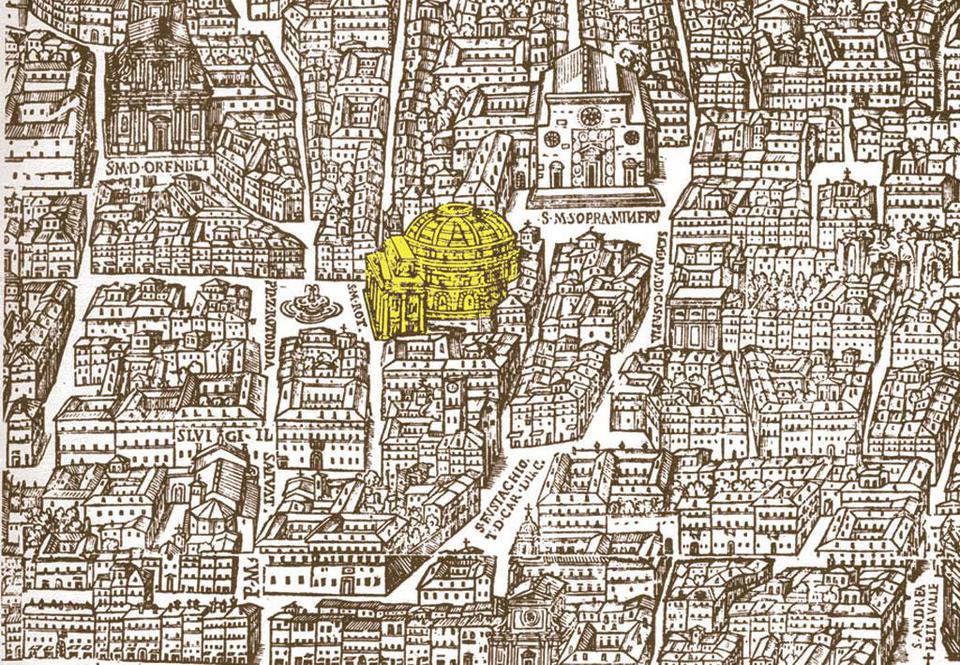

In truth, no one knows the Pantheon’s exact age. One legend says that the first Roman citizens built the original Pantheon on the very site where the current one still stands in the Campo Marzo—modern Rome’s business district. The ancients constructed this first Pantheon after Romulus (753–716 B.C.), their mythological founder, ascended to heaven from that site. They dedicated it to Romulus and some of his divine ancestors and, for centuries, held rites and processions there.

Most historians, however, claim that Emperor Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built the first Pantheon in 27 B.C., a rectilinear, T-shaped structure, 144 feet by 66 feet (44 m × 20 m), with masonry walls and a pitched timber roof. It burned in the great fire of 80 A.D., was rebuilt by Emperor Domitian, but was struck by lightning and burned again in 110 A.D.

Visitors are dwarfed by the columned portico. Millions tour the structure annually making it the most visited historical site in Italy.

Visitors step through two giant, 25-foot-tall cast bronze doors to enter the central rotunda of the Pantheon. These enormous doors are so balanced that one person can push or pull them open.

An elegant emperor

Seven years later, Hadrian, the adopted son and successor of Emperor Trajan, became Rome’s ruler. Hadrian was elegance personified. He was tall and strong, had his hair curled and his full beard groomed daily. Moreover, Hadrian saw himself as a divinely inspired poet, with an avid interest in Hellenic culture, especially literature, music and architecture—so much so that his contemporaries snidely called him “the Greekling.”

By 120 A.D., Hadrian began designing a Pantheon reminiscent of Greek temples and far more elaborate than anything Rome had yet seen. His plans called for a structure with three main parts: a pronaos or entrance portico, a circular domed rotunda or vault, and a connection between the two. The rotunda’s internal geometry would create a perfect sphere since the height of the rotunda to the top of its dome would match its diameter: 142 feet (43 m). At its top, the dome would have an oculus or eye, a circular opening, with a diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m), as its only light source.

Hadrian said, “My intentions had been that this sanctuary of All Gods should reproduce the likeness of the terrestrial globe and of the stellar sphere…The cupola…revealed the sky through a great hole at the center, showing alternately dark and blue. This temple, both open and mysteriously enclosed, was conceived as a solar quadrant. The hours would make their round on that caissoned ceiling so carefully polished by Greek artisans; the disk of daylight would rest suspended there like a shield of gold; rain would form its clear pool on the pavement below, prayers would rise like smoke toward that void where we place the gods.”

Hadrian visualized himself enthroned directly under the Pantheon’s oculus—a near-deity around whom not only the Roman empire but the universe, the sun, and the heavens obediently revolved.

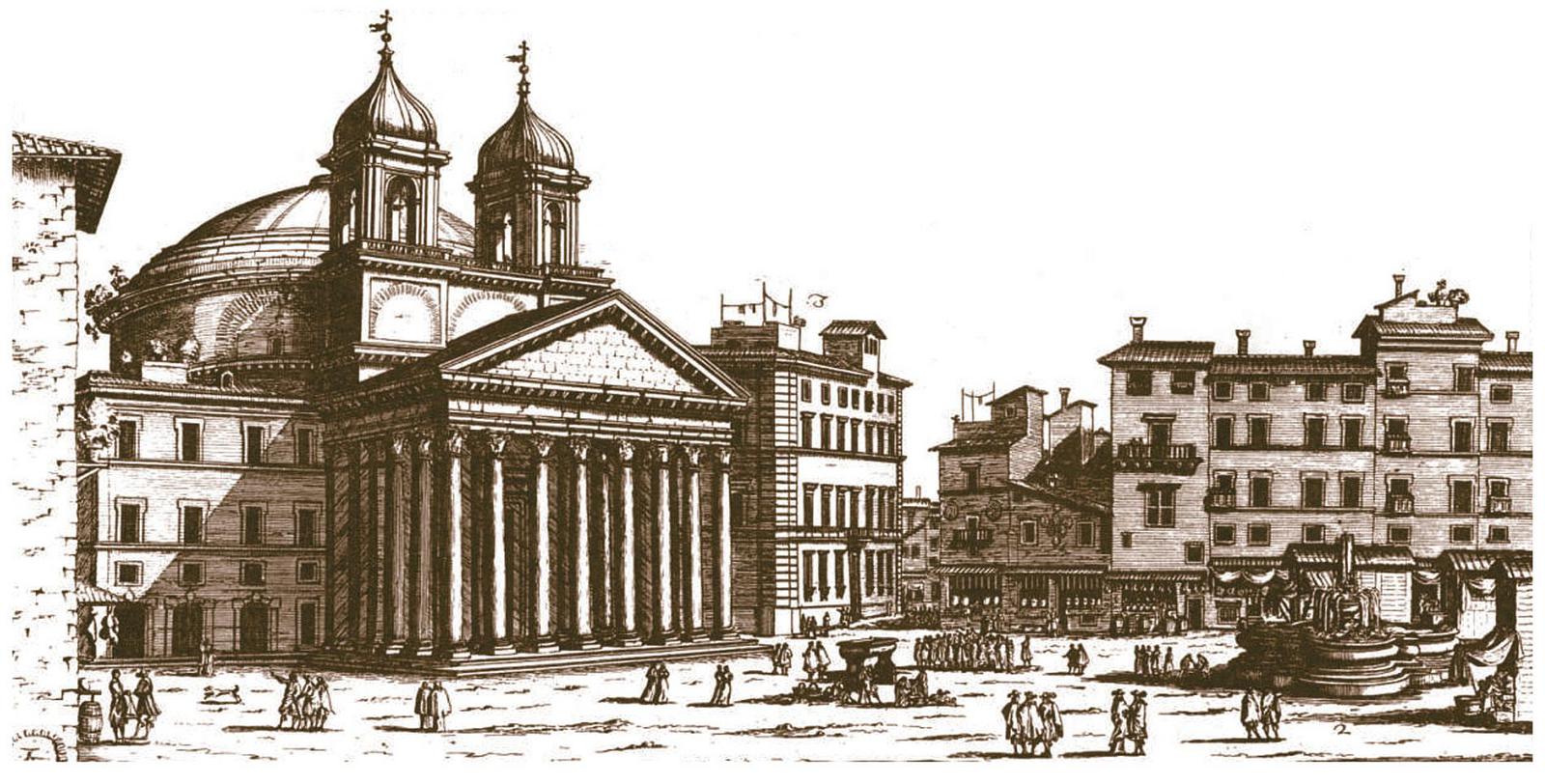

Using the design of Alessandro Specchi, Pope Clement XI (1700–1721) rebuilt the high altar and apse in the sanctuary. The Pantheon, dedicated as a Catholic church and renamed Santa Maria ad Martyres—Our Lady and the Martyrs—has several small chapels, each decorated with priceless artwork

Work begins

Hadrian’s engineers began clearing the site and preparing the foundations. They dug a circular trench 26 feet (8 m) wide and 15 feet (4.5 m) deep for the rotunda’s foundation and rectangular trenches for the pronaos and the connector. They lined the trenches with timber forms and layered those with pozzolana cement—a powerful cement that the Romans discovered they could make by grinding together lime and a volcanic product found at Pozzuoli, Italy.

Though the Romans had been building with concrete since about 200 B.C., work on the Pantheon was difficult and proceeded in gradual stages. Other buildings surrounded the site, so laborers lacked space in which to work.

Sunlight streams through the 30-foot (9.1 m) diameter oculus atop the 142-foot (43 m) hemispherical dome interior.

They also lacked machinery. Vitruvius (circa 20 B.C.), a noted Roman architect, recorded the process followed in his day, that was probably still used by the Pantheon’s builders. The ancients hand-mixed wet lime and volcanic ash in a mortar box, adding very little water so that they got a nearly dry composition. They carried this mixture to the job site in baskets and poured it over a prepared layer of rock pieces. They then tamped the mortar into the rock layer. The tamping packed the mortar, reduced the need for excess water, but, at the same time, stimulated bonding.

Transportation presented another problem. Just about everything had to come down the Tiber by boat, including the 16 gray granite columns Hadrian ordered for the Pantheon’s pronaos. Each was 39 feet (11.9 m) tall, 5 feet (1.5 m) in diameter, and 66 tons (60 t) in weight. Hadrian had these columns quarried at Mons Claudianus in Egypt’s eastern mountains, dragged on wooden sledges to the Nile, floated by barge to Alexandria, and put on vessels for a trip across the Mediterranean to the Roman port of Ostia. From there, the columns were barged up the Tiber.

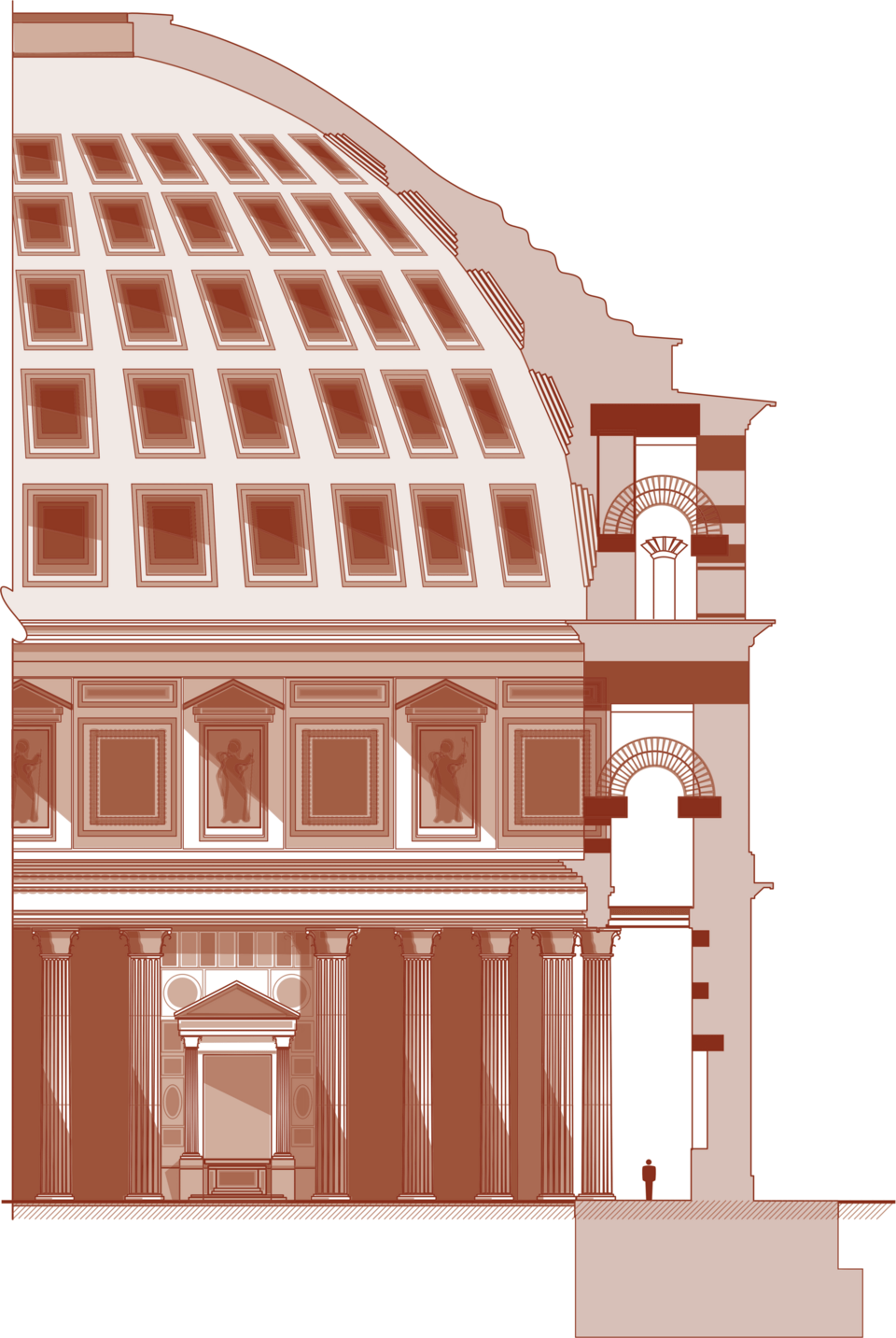

The concrete dome is 20 feet (6 m) thick at the base and tapers to 7.5 feet (2.3 m) thick at the oculus. Without materials like rebar to hold the dome in tension, the massive concrete rings create a buttress-like effect that forces the dome into constant compression. The concrete dome weighs an astounding 5,000 tons (4,535 t).

A concrete dome

An illustrated cross-section helps convey the massive scale of the Pantheon. The foundations are 24 feet (7.3 m) thick at the base and stepped back to 21 feet (6.4 m) at ground level. The interior fluted columns are 3 feet (0.9 m) in diameter by 29 feet (8.8 m) tall, topped with a 4 foot (1.2 m) tall Corinthian capital—totaling 33 feet (10 m) tall at 25 tons (22.7 t) each. And the Portico has 16 granite columns, 5 feet (1.5 m) diameter by 39 feet (11.9 m) tall weighing 66 tons (60 t) each.

Eventually, work began on the concrete dome, constructed in tapering courses or steps that are thickest at the base (21 ft / 6.4 m) and thinnest at the oculus (7.5 ft / 2.3 m). The Romans used the heaviest aggregate, mostly basalt, at the bottom and lighter materials, such as pumice, at the top.

They embedded empty clay jugs into the dome’s upper courses to further lighten the structure and facilitate the concrete’s curing.

In the dome’s construction, the Romans probably used temporary wooden centering on which they layered concentric rings of masonry and concrete.

Through the ages, engineers have theorized about the centering. Some say the Romans used heavy wooden scaffolding, throughout the construction process, that reached from the floor to the oculus.

Others believe that centering was not required for the lower third of the dome, so the Romans used a lighter centering system supported from the dome’s interior, second cornice line.

To create the dome’s oculus, which acts as a compression ring, the Romans built two circles of bipedales, handmade bricks that were 24 inches (60 cm) square and 1.57 inches (4 cm) thick. They laid the bipedales edgewise in three vertical courses, then circled the oculus with a bronze cornice.

The oculus was not the only feature that got a bronze treatment. Hadrian had the original roof bronze-tiled and the Latin lettering on the entablature inscribed in bronze. It read: M AGRIPPA L F COS TERTIUM FECIT, which translates to “Built by Marcus Agrippa, the son of Lucius, third counsul.”

Drawing by Giovanni Battista Falda from the late 17th century. Pantheon is defined as a temple to all gods. Pope Urgan VIII (1623–1644) added the two bell towers designed by Bernini. They were removed in 1833.

An enduring mystery

Why the egotistical Hadrian insisted on crediting his predecessor for the Pantheon remains an unsolved mystery. Some believe he did it as a symbolic gesture that reinforced his connection to Rome’s ancient imperial line.

But the Pantheon presents yet another, far greater mystery. Why, after nearly 2000 years, is this structure, built on marshy land, with a dome whose span was not surpassed for hundreds of years, still standing?

Theories abound. Some believe the Pantheon is divinely protected. Until the 5th century, it was a temple dedicated to all the Roman gods. In 609 A.D., Emperor Phocas gave it to Pope Boniface IV, who consecrated it, dedicated it to St. Mary and all the Christian martyrs, and renamed it Santa Maria ad Martyres.

One of at least eight paintings (circa 1734) by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765) of the Pantheon, a popular subject among collectors. Centuries later the fashions have changed, but the structure is the same.

While the Pantheon may be divinely protected, there are more earthbound reasons for its survival as well. It was built of very strong concrete with pozzolana cement. A gradation process was used so that the structure is heavier at the bottom and much lighter at the top. The dome’s oculus or opening lightens the load and acts as a compression ring.

Whatever the reasons, the Pantheon is the only structure of its age, size and span that has successfully survived the scourge of time and gravity and has come down to us, intact, and in all its splendor and beauty. Like Michelangelo, we too can look at the Pantheon and marvel at this wonder that looks more like the work of angels, not humans.

The Monolithic Dome and The Pantheon

The Pantheon is the spiritual ancestor of all domes and as a one-piece concrete structure, a monolithic dome. It took over a decade to build and an extraordinary volume of concrete. Modern Monolithic Dome construction offers some distinct advantages the ancient builders never had.

Inflatable Forming—The Romans created the Pantheon’s form with earthworks and timber—an arduous, time-consuming process. We can inflate a giant Airform in less than two hours. The Airform has the additional advantages of being portable and ultimately becoming the roof membrane of the finished structure.

Concrete—The Pantheon’s concrete was a mixture of pozzolan, lime and a small amount of water. That mixture was tamped—not poured—into place. Today, we have portland cement, which is easily ten times stronger and much easier to work with.

Steel Reinforcing Rebar—All concrete is weak in tension. We strengthen our concrete with reinforcing steel bars—rebar. The Romans did not have that option. They used ropes of vitreous china for reinforcement. To further compensate for the weakness and weight of the concrete, the Romans built extremely thick footing and drum walls. Otherwise, the weight of the dome would have spread the vertical walls of the drum and the Pantheon would not have lasted.

Reprinted from the Summer 2001 issue of the Roundup: Journal of the Monolithic Dome Institute. Story posted and updated with new photographs on July 21, 2021.