A Closer Look at the Birth of the Monolithic Dome

The birth of a dream

When I was a junior at Idaho Falls High School in 1956, I listened to a speech by Buckminster Fuller about how domes were the answer for big buildings across the world and how they were going to be the solution to much of the globe’s problems. He described the geodesic dome in detail and its construction methods, and I caught his vision and became a dome enthusiast.

I began building geodesic domes out of toothpicks, drinking straws, and erector sets. I also started learning the mathematics needed for engineering domes. I quickly learned that I hadn’t had enough math instruction, so naturally, I went to my high school teachers and asked them if they could do the math—they couldn’t either.

While in college in 1959, I married my wife, Judy, and I began playing with the geodesics in earnest. I could see that Buckminster Fuller was right—they could be a real answer for structures. It seemed natural to ask my college professors if they could do the mathematics associated with dome engineering, but the math proved difficult enough that they were not much help either. I managed to call Fuller, but he didn’t have time to speak with me. I was disappointed but still determined.

During this time, to support my small family and pay for college, I was very busy selling real estate and running the family sawmill. Consequently, domes were pushed further and further down my priority list. Still, over the years, I continued to learn more about dome engineering.

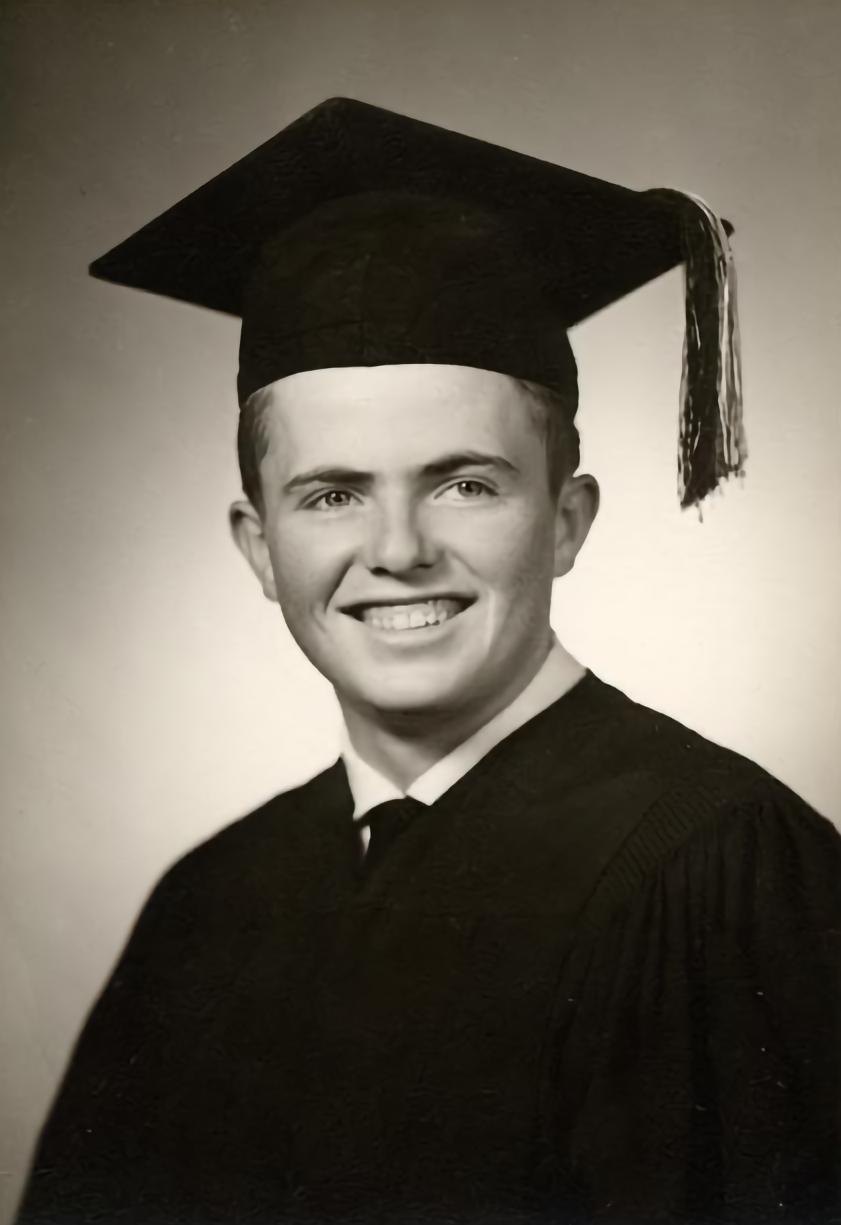

David B. South in an RCA publicity photo taken in 1968 of the computer center at Chicago Northwestern Railroad in Chicago, Illinois.

Chicago and the introduction to polyurethane foam

Before I realized my dream of building big domes, I did a lot of other things. I went to Idaho State University, where I earned a Bachelor of Business Administration. Then we moved to Chicago, Illinois, where I worked for Chicago Northwestern Railway managing their computer center.

Halfway through the summer of 1970, I decided to move back to Idaho. My mother was a widow with six children, me being the oldest. I felt that I needed to be back home, helping her. So, even though I had not decided what I would do to make a living in Idaho, I turned in my resignation.

The week before I was slated to leave Chicago, my assistant showed me a beautiful statue that looked like it was carved out of a hardwood. She handed the statue to me, and to my surprise, it weighed almost nothing. I asked her about the “wood,” and she explained to me that it was cast from polyurethane foam and that there was a seminar down the street where they were teaching about polyurethane foam casting. My mind jumped immediately to the possibility of casting the triangular sections needed to build a geodesic dome.

I went to the seminar, and near the end, they showed a video of spraying the polyurethane foam for insulation. What a spectacular insulation it was! The polyurethane was waterproof, “virtually fireproof,” and it was by far the best insulation that I had ever seen before. Before and during college, I spent time building traditional houses insulated using conventional insulation. With one view of this video, I knew the polyurethane was, by far, superior to any other form of insulation I had seen. Right then, I knew that my future was going to be tied up with polyurethane.

A 1971 picture of Barry Jones—the South’s 10-year-old cousin—holding a polyurethane “boulder” above his head, steadied by Randy South.

The move to Idaho

The next week, I moved to Idaho, and of course, my first task was to find something that would make some money. I already had four kids and one on the way, and I knew it was going to take money to keep the household running smoothly. So, I began studying polyurethane foam in-depth and found a company in Utah that had some of the equipment available. The concrete company president offered to finance an insulation loan if the polyurethane worked on concrete buildings, as it would allow them to expand. This helped us make the decision to start a urethane foam division that I would run.

We outlined a plan showing that we could probably sell twenty thousand dollars worth of this polyurethane foam in a year. I bought a used two-ton truck with a box bed and put all the equipment inside. I then bought some urethane in fifty-gallon drums and hit the ground running. I sold twenty-thousand dollars worth of projects in the first six weeks and had all the foam applied in eight weeks.

South’s, Inc. headquarters in Shelley, Idaho, in 1976 with one of the company’s polyurethane foam trailers out front.

The business of insulating potato storages

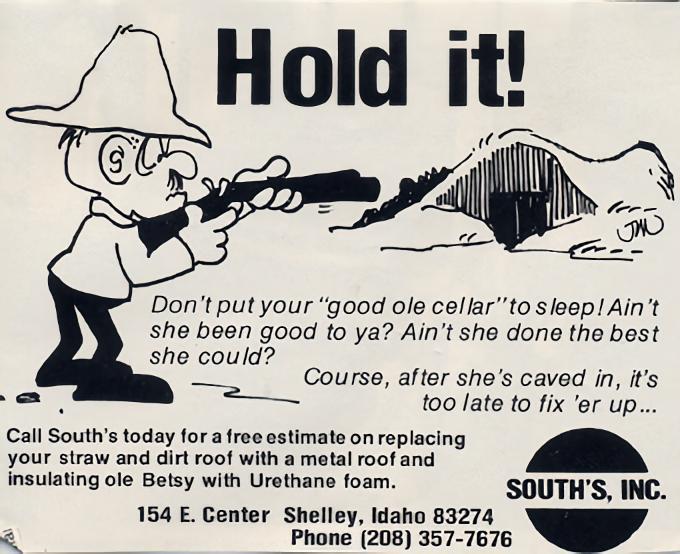

A South’s, Inc. potato cellar urethane insulation advertisement that ran in the early 1970s in the Potato Growers Magazine.

The need for polyurethane foam in Idaho was enormous, with potato storage owners being one of the major customers. Idaho has over four thousand potato storages. One of the reasons for the high demand is the amount of moisture potato storages collect inside. This means that if conventional insulation is used in the storage, the insulation will become saturated, and the insulation value drops out of sight. The polyurethane, being waterproof, proved to be a solution to the insulation problems the potato storage owners were having. Polyurethane foam is so waterproof you could use it to line your boat if you did not want it to leak.

By the next year, 1971, my brothers—Barry and Randy—and I decided to start our own urethane foam company. It soon proved to be a solid investment, and the business thrived. This meant I could now take care of my family and help other people, as well. There continued to be a great demand for better potato storage insulation, and we continued selling polyurethane, trying to meet the demand. The cost of insulating an average potato storage in 1971 was twenty-thousand dollars. Before long, we had more equipment and more crews. We expanded the scope of our business, insulating freezers, and some houses. The business was good.

The polyurethane foam Bald Eagle created by Barry, David, and Randy South for the July 4, 1976, Bicentennial Parade in Idaho Falls, Idaho.

Foam domes

After learning about urethane foam and before moving to Idaho, I read an article in a magazine about a dome home in Wisconsin built entirely of foam. The man who built it was a polyurethane foam spray contractor and did a lot of insulating.

The Xanadu House in Kissimmee, Florida, is a demonstration home built using polyurethane foam as the primary structural component. There were other “foam homes” constructed in Wisconsin, Tennessee, California.

As we started our urethane foam business in Idaho, I struggled with the idea of building foam domes. We’d worked out how to do it ourselves. The bigger problem is that while polyurethane foam is strong, it’s not strong enough to build really big domes. Foam domes would always be limited in size. Thus, I discarded the idea of a foam dome.

Our little geodesic dome

In 1974, we built a 30-foot geodesic dome to be used as a storage in my backyard in Taylor, Idaho. I was still enamored with the geodesic domes and wanted to make sure I had all the math and construction methods worked out. Even as enamored as I was, I was beginning to be very discouraged with the geodesics.

The geodesic dome is made by cutting out lumber and forming it into the shape of a dome. The amount of waste is just terrible. At the time I built my geodesic storage, there were a number of geodesic domes that had been built, and I talked to various people that had them. I don’t think I talked to anybody with a geodesic dome that didn’t say as their first comment, “Mine leaks,” or “Mine doesn’t leak.”

The millions of little pins and joints make the geodesic domes, generally, leakers. The builder has to be very, very careful that he doesn’t leave any leak points when during construction. It was a good idea to build that geodesic storage in my backyard, and I learned a lot, but by the time I got that dome built, I did not want to build any more geodesics. We continued to spray foam full-time.

Eventually, after developing the Monolithic Dome, I found a couple of geodesic dome books—Domebook One and Domebook Two—written by Lloyd Kahn. Kahn’s books contained all the math needed to build a geodesic dome, but by the time I read them, I had already made my mind up to build Monolithic Domes instead. It is interesting to note that Kahn wrote an article called, Smart But Not Wise—Further Thoughts on Domebook Two, Plastics, and Whiteman Technology, a year after publishing Domebook Two. In this article, he admitted the shortcomings of the geodesic dome.

Kahn said, “Metaphorically, our work on domes now appears to us to have been smart: mathematics, computers, new materials, plastics. Yet reevaluation of our actual building experiments, publications, and feedback from others leads us to emphasize that there continue to be many unsolved problems with dome homes. Difficulties in making the curved shapes livable, short lives of modern materials, and as-yet-unsolved detail and weatherproofing problems.”

I felt the Monolithic Dome methods would solve many of these problems.

A potato cellar—lined with polyurethane foam—caught fire in 1974. The foam contained the heat creating a runaway fire that completely destroyed the building.

Not so fireproof foam leads to a new direction

By 1975, I was thinking about domes again because of a difficult challenge in the polyurethane foam industry—that “fireproof foam” was not so fireproof after all. Polyurethane foam doesn’t burn very well. Foam will not sustain a fire when it’s out in the open. But if the foam is exposed on the inside of a building—like in a potato storage—the foam is such a super insulation, it traps the heat inside if there is a fire. The fire builds up heat, which cannot escape—the temperatures skyrocket. Then the foam will almost explode because there is nowhere for the built-up heat to go.

After learning this, we started spraying a layer of stucco or plaster—about a half an inch thick—over the polyurethane surface inside some of the potato storages. The amount of strength that plaster gave was just phenomenal, and of course, one thought leads to the next, and suddenly you say, “Oh, why don’t we just spray it with the concrete?”

A layer of concrete made the foam fire-safe, but we also realized that if we sprayed the concrete thicker, we would have a building.

The advent of the Monolithic Dome

Of course, I had heard about the man who had built his house by inflating a balloon made out of some kind of plastic and then spraying the inside of it with three- to six-inches of polyurethane foam. The more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea of using an inflated form. However, we would be building out of foam and concrete. Additionally, with the concrete, it could be a big building.

My brothers and I hired a local engineer to develop a 105-foot diameter by 35-foot tall dome for a potato storage. With our design and his modifications, we decided to spray three-inches of polyurethane foam on the inside of a fabric air-formed membrane. Next, we planned to spray three-inches of concrete, reinforced with rebar.

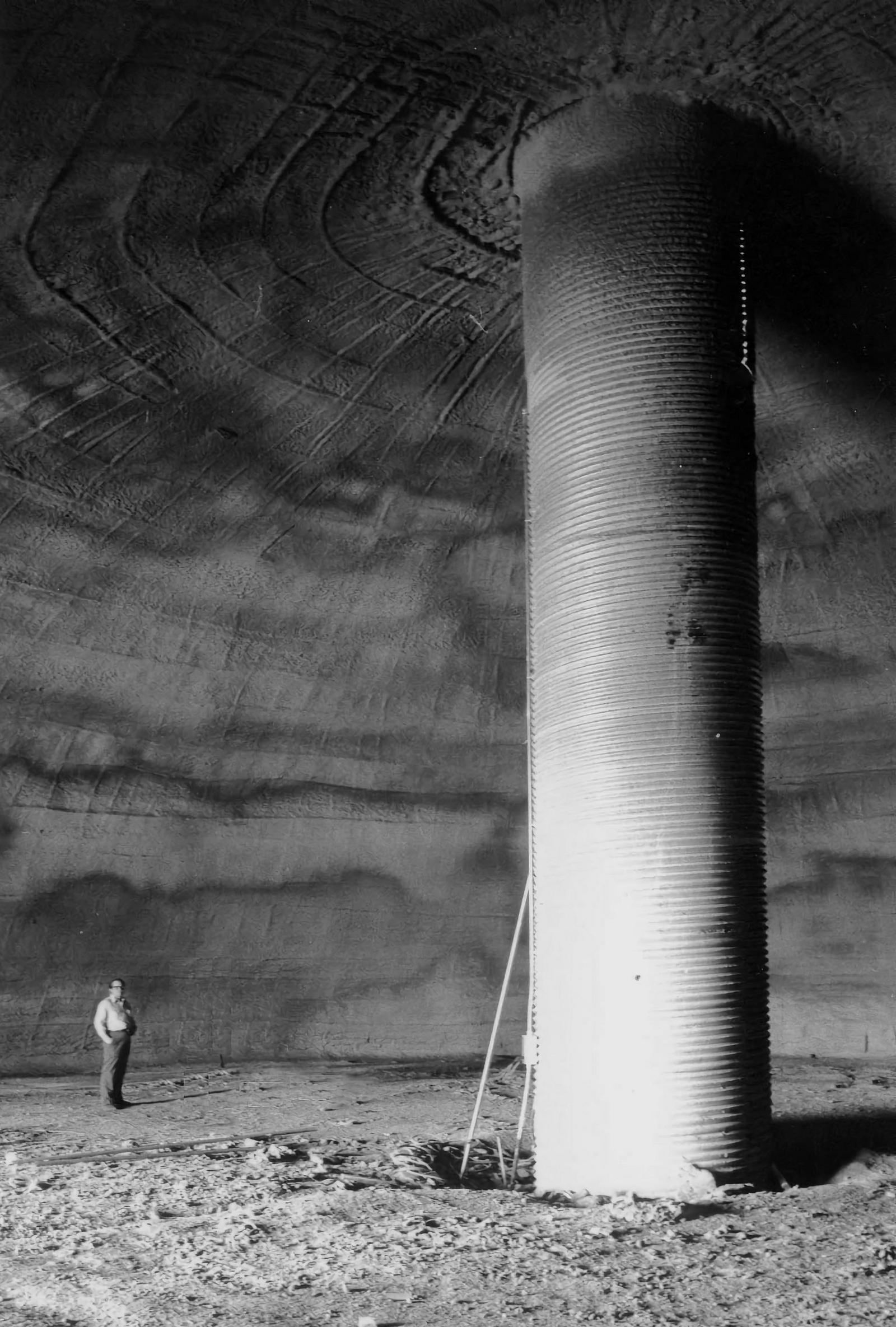

The fabric dome-shaped membrane attached to the circular foundation. The tall cylinder is an air plenum used to maintain a consistent climate for potatoes that will be stored in the dome. For construction, the air plenum fans will inflate the fabric membrane.

The fans in the air plenum are on and the membrane is inflating to create the shape of the first dome.

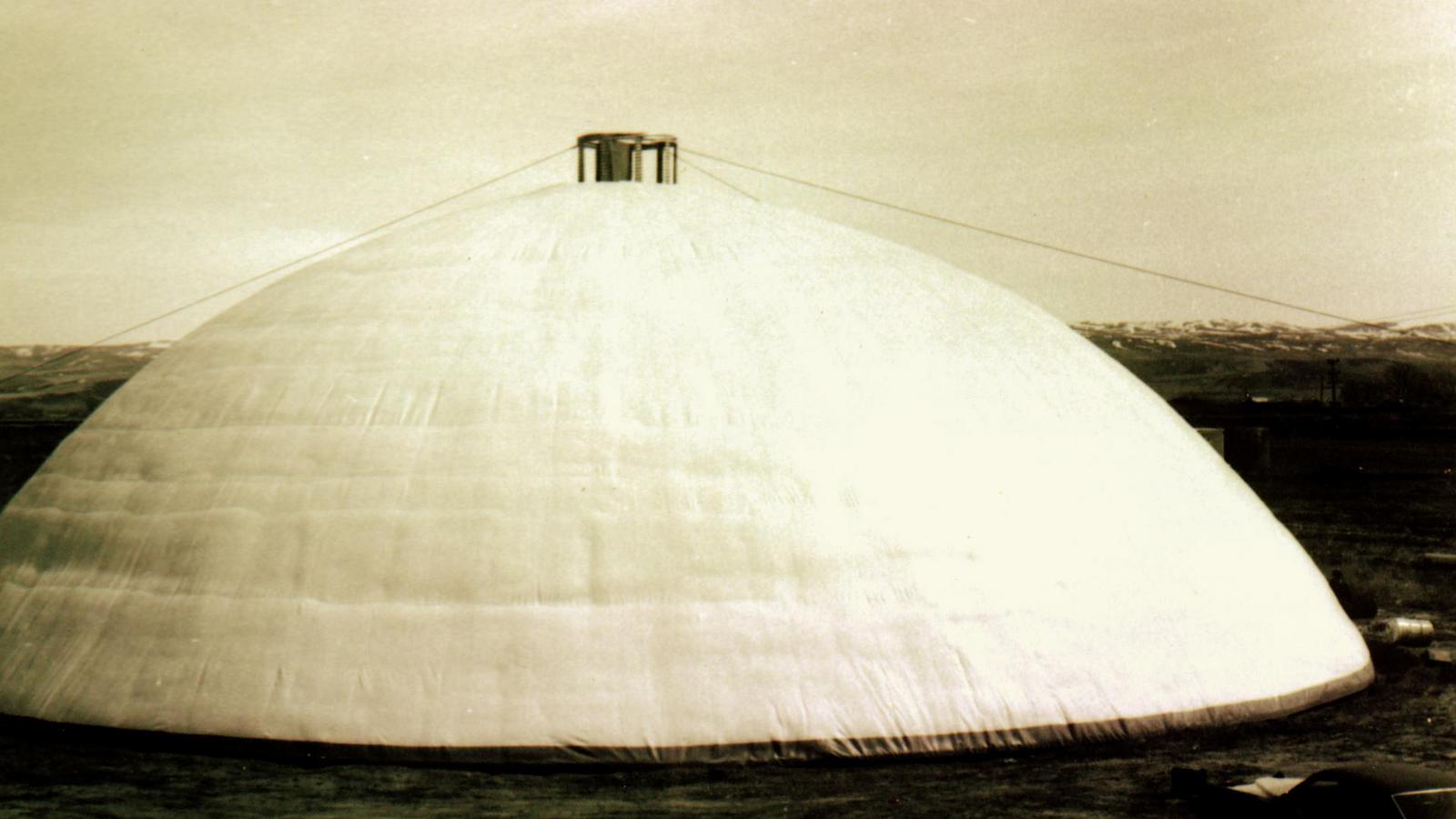

The fully inflated air-form membrane for the world’s first Monolithic Dome—a potato cellar in Shelley, Idaho. The dome is 105-feet diameter by 35-feet tall.

The air-formed fabric membrane

To implement the design, we had to find someone who could manufacture the fabric “balloon.” After some searching, we found a company in California who manufactured inflatable bounce houses—the kind you see at children’s parties all over the world. This company, subsequently, built several of the inflatable membranes for us.

We thought it would be a good idea to reuse the membranes to build more domes, so the first several membranes we received, we peeled off the domes after they were constructed. In theory, this was a good idea, but we learned that after the membrane was peeled off, the urethane had to be coated for protection. These coatings were far less effective—and more expensive—then leaving the membrane in place.

Later, I got in touch with Jack Boyt at Precision Air Structures in Des Moines, Iowa. We forged a friendship as he developed the techniques to really build the air-form membranes.

Construction of the first Monolithic Dome

Our first Monolithic Dome was a potato storage in Shelley, Idaho. As a potato storage, the insulated dome proved to be spectacular. No other potato storage was even close to being as well insulated.

This first dome was built with an eight-foot diameter pipe that rose from the ground in the center of the dome, then up and out of the top of the dome. The pipe was the air handling column for the air going in to ventilate the potatoes. Twenty feet up that column, we put a very large fan designed to handle all the air it would take to ventilate the 50,000,000 pounds of potatoes.

The air was drawn in from the top—literally from outside the dome—and expelled at the bottom in a series of 16-inch pipes that formed a fan shape on the floor of the dome. This made it so when the air came down, it went through the fan shape and then was dispersed under the potatoes.

Now, this unit was fairly complex because it had air intakes that reached to the outside to pull the air in, but just under the roof of the dome, there was another set of air intakes. These two sets of air intakes were beveled so they could bring in total outside air or total inside air. In general, you brought in mixed air so it would assure the air going into the potato pile would be roughly the temperature you would want the potatoes to be kept. This was all electronically monitored, and the mechanisms that shifted the air back and forth were very sophisticated.

We had been building these air systems for ventilating conventional potato storages for several years. In constructing our first two Monolithic Dome potato storages, we decided we could use the ventilation system to inflate the air-form membrane.

Construction of the first Monolithic Dome was finished in April 1976. The new structure will store over five million pounds of potatoes.

By the time we were designing the third Monolithic Dome, we realized we could not rely on that electric fan to inflate the form because once in a while, the power would go off. We found the solution by coming up with an exterior set of inflators that could run with gasoline or diesel as well as electricity. By running two fans, the chances of a sudden power loss to knock out the dome inflation were ten times better.

The rebar attachment on this first dome was very similar to what we did on later domes. The big difference was, we used a bent wire and fed it through the urethane foam as a rebar hanger. It was much slower than what we are presently doing, but it did work.

By the time we finished our first dome, we figured out how to use an insulation anchor. The insulation anchor we used in those days was one that was built for commercial insulation anchorage to metal plenums. We had to glue this anchor to the urethane with caulking. We eventually developed a way of bending pieces out of the bottoms where we could attach a rebar hanger simply by pushing it into the polyurethane foam.

Michigan for the second dome

That summer, I got a call from Bud DuRussel in Michigan. He had seen an article written about our first potato storage in the Idaho Potato Grower magazine. He said, “I want one. I am growing potatoes here in Michigan, and I need a place to store them, and this looks like the best option.”

I told him that my first business was spraying polyurethane, and I really did not have the time. In addition, I had reservations about traveling to Michigan to build the dome. Bud told me he understood, and we ended the call.

The next day, Bud called back saying he wanted the Monolithic Dome and that he wanted me to come build it. He assured me it would work out and that he would take care of all the paperwork. I talked him out of it once again.

When the phone rang the next day, I was surprised to find Bud had called back. “What do I have to do to get you to come build that building?” he demanded.

I suggested he wire 5,000 dollars to me, and I would use some of the money to fly out and look at his property and situation. I told him, “We’ll talk to each other, and we will make a decision together. If the decision is to build the dome, we will build it. If the decision is not to build it, then we will say ‘goodbye,’ and I will give you all of your money back except for the price of the plane ticket.”

A half-hour later, my banker called and said, “We just got a wire transfer from Michigan for five thousand dollars.”

I called Michigan, set up the appointment, and away I went. Needless to say, we made the deal, and we had the dome to build. We also had all our insulation jobs back in Idaho to take care of. So, we laid out our plans on how we were going to do it. We sent two people in the crane truck pulling the foam trailer out to Michigan. I then got in my Beach Bonanza and flew to Michigan with three others of our crew.

When we got there, I bought a pickup so I could send the foam machine back. Within a few days, we had the foaming all done and had sent the “new” used pickup truck back pulling the foam trailer, with two of the crew.

The rest of us finished up building the Michigan dome. It was a spectacular building, and we were only gone seventeen days from the time we left Idaho to when we got back. That time-frame for constructing a complete building was like magic.

We built a second dome for Bud DuRussell, and by the end of construction, I knew that dome-building was what I wanted to do full-time. I felt I had received inspiration that this was the building for the future.

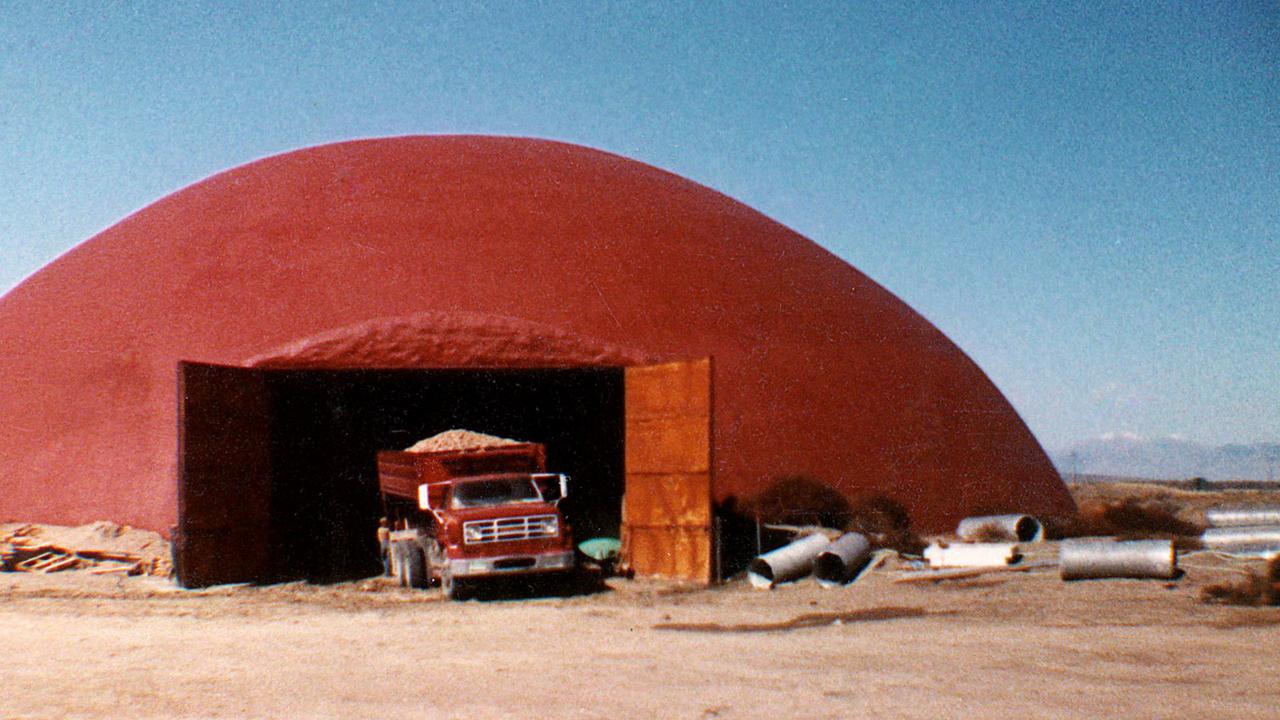

Another 105-foot by 35-foot potato cellar in Hamer, Idaho, built in the early days of the industry. By now the South’s had abandoned their insulation business, they co-patented the Monolithic Dome, and they started Monolithic Constructors, Inc. to build Monolithic Domes full-time.

Monolithic Constructors, Inc. / Monolithic Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

The next dome we built was a home for our mother, Marjorie South, on the South Menan Butte.

From then on, we started marketing the domes and cutting back on selling polyurethane. By the end of the next year, we had pretty well gotten out of the foam business, and I was simply selling and building the Monolithic Domes.

My brothers and I were granted patents for the Monolithic Dome construction process in 1979 and 1980.

Worldwide construction process

It was my dream to build big domes and build them everywhere. As of 2014, there are thousands of Monolithic Domes built in 49 states and 53 countries. Every dome is unique—gymnasiums, schools, stadiums, houses, rental units, bulk storages, and many more.

The Monolithic Domes are super-insulated, energy-efficient, and have the ability to survive virtually any natural or manmade disaster. They offer solutions to social problems and concerns, such as our nation’s dire need for safe, clean, affordable housing. Still, we have ongoing research and test new products, striving to perfect the world’s greatest building—the Monolithic Dome.

This story republished from The President’s Sphere blog.